#3 OOP Series: Relationships and Associations, Part 1

In this series, I will go over the principles and foundations of object-oriented programming and some principles on databases.

In this series, I will go over the principles and foundations of object-oriented programming and some principles on databases. I will be using Ruby because I feel comfortable in the language; however, these concepts with some minor changes in syntax can be translated to other object-oriented programming languages, like Java, Node.js, etc.

Hello again!

If you're in New York, I hope you're staying warm and productive especially with all of this snow.

This blog post is all about relationships and associations and I swear I didn't plan for it to be published during this time. However, I supposed it fits well in the season.

This is also the part of the series where you should be thinking about whether or not you want to use a relational database, like PostgreSQL, or non-relational database, like NoSQL. Non-relational databases don't need associations between objects because you're running queries against the database.

Let's get started!

OOP and Relational Databases

If you have been following along with your codebase, this will blog post and the next one will be very interesting for you.

When you think about relationships and/or associations objects, it's very much modeled on the real-world. For instance, if we take our Person and Dog classes from past blog posts, we can create a relationship between the two.

Let's first add our classes here.

Person.rb

class Person @@all = [] attr_accessor :name, :age, :height def initialize(name, age, height) @name = name @age = age @height = height #* height in inches @@all << self end def self.all @@all end def say_name puts "My name is #{self.name}." end def say_age puts "I'm #{self.age} years old." end def say_height puts "I'm about #{self.height} inches tall." end end alex = Person.new("alex", 26, 68)

Dog.rb

class Dog attr_accessor :name attr_reader :breed, :age @@all = [] def initialize(name, age, breed) @name = name @age = age @breed = breed @@all << self end def speak puts "Bark! I'm a #{self.breed}" end end dog1 = Dog.new("Rover", 3, "Poodle")

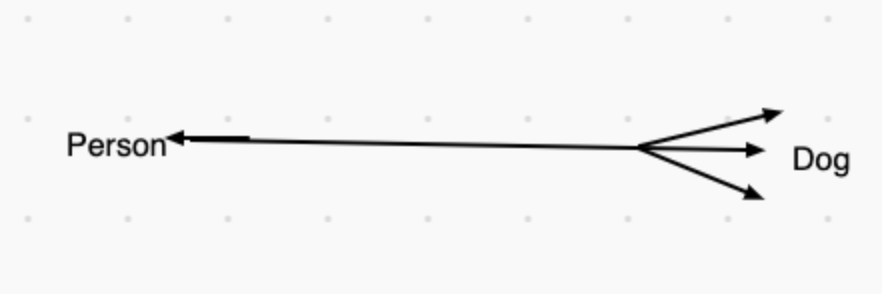

As it stands right now, we have a person and a dog but there's no relationship between them. We can say that a person can have many dogs, but a dog has one person (owner).

Above, you can see an illustration of a person that can have many dogs, but a dog currently only has one person or owner.

Single Source of Truth (SSOT)

One of the most common practices in information systems design and theory is the concept of Single Source of Truth (SSOT). It simply means that the information in our database is accurate and correct. In the case of our Person and Dog classes with their has-many relationship, a dog can't be claimed by more than one person and have more than one owner.

Attributes

We need to update our Dog class' attributes to include an owner attribute now. We'll list it with the attr_accessor method because a dog can have no owner and then be adopted. Let's take a look at our updated Dog class:

class Dog attr_accessor :name, :owner attr_reader :breed, :age @@all = [] def initialize(name, age, breed, owner) @name = name @age = age @breed = breed @owner = owner @@all << self end def speak puts "Bark! I'm a #{self.breed}" end end dog1 = Dog.new("Rover", 3, "Poodle", "No Owner (Yet)")

We added our owner attribute to the Dog class.

We're going to update our Person class slightly.

require 'pry' class Person @@all = [] attr_accessor :name, :age, :height def initialize(name, age, height) @name = name @age = age @height = height #* height in inches @@all << self end def self.all @@all end def say_name puts "My name is #{self.name}." end def say_age puts "I'm #{self.age} years old." end def say_height puts "I'm about #{self.height} inches tall." end def adopt_a_dog(dog_instance) dog_instance.owner = self end def buy_a_dog(name, age, breed) # (name, age, breed, owner) #! the values for the Dog class initialize method Dog.new(name, age, breed, self) end end alex = Person.new("alex", 26, 68)

We created two new instance methods, adopt_a_dog and buy_a_dog. (Remember, an instance method doesn't use the keyword self in the name, unless it's going to be a class method.) Our instance method adopt_a_dog takes in an argument of dog_instance and sets the owner attribute of that instance of Dog equal to the self (the instance of Person). Sadly, our dog1 instance, Rover, doesn't have an owner yet.

Helpful Tip — Create a file called console.rb (the name isn't important) and use require_relative to import your models so you can have them interact with each other easily.

console.rb

require 'pry' require_relative './app/models/dog.rb' require_relative './app/models/person.rb' alex = Person.new("alex", 26, 68) dog1 = Dog.new("Rover", 3, "Poodle", "No Owner (Yet)")

We can adopt dog1 when we invoke the adopt_a_dog method that alex has access to.

alex.adopt_a_dog(dog1) #=> #<Person:0x00007fbe93463968 @age=26, @height=68, @name="alex"> dog1 #=> #<Dog:0x00007fbe934638c8 @age=3, @breed="Poodle", @name="Rover", @owner=#<Person:0x00007fbe93463968 @age=26, @height=68, @name="alex"

As you can see, when we call dog1 a second time, the owner attribute is no longer equal to "No Owner (Yet)." It's equal to alex.

We want to set the owner attribute an object instead of a name because this is part of having an application with a Single Source of Truth. Multiple people can be named "Alex", but they're obviously not the same person and can't/shouldn't be so interchangeable. If for any reason we needed access to the name of dog1's owner, we would method chain, like so: [dog1.owner.name](http://dog1.owner.name) and it would return "alex".

Conclusion

This is a simple way to construct a relationship between two models. There are other ways, like has-one and has_many_through. Next week's post will involve creating a many-to-many relationship.